Baltimore Oriole

General Description

The Baltimore Oriole breeds across southern Canada and the United States east of the Rocky Mountains and winters mostly from central Mexico to northwestern South America. It hybridizes with Bullock’s Oriole in a narrow zone where their ranges meet in the Great Plains, and as a result, the two were once lumped together as a single species (“Northern Oriole”). However, the American Ornithologists’ Union split them again in 1995 on the basis of genetic studies that showed them not even to be one another’s nearest relatives.

The adult male Baltimore Oriole is bright orange with a black hood and back and a large white wingbar. The adult female has a grayish crown and back and two white wingbars. The underparts range in coloration from almost as bright orange as the male in some individuals to a light orange-yellow in others. Immatures generally resemble adult females; consult field guides for separating these plumages from Bullock’s and other orioles.

Baltimore Oriole breeds in northeastern British Columbia, east of the Rockies, but occurs only casually elsewhere in the province. Three of Idaho’s four records are from May–June; the other is from mid-August. Washington also has four records, three of them between 31 May and 20 June and the other in early November; two are from east of the Cascades and two are from the Westside. Half of Oregon’s ten records are from fall and winter and the other half are from spring.

Revised November 2007

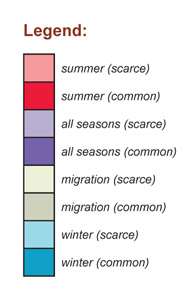

North American Range Map

Family Members

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus

Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor

Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta

Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus

Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus

Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus

Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula

Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus

Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater

Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius

Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus

Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii

Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula

Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum

Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum